Our morning drive along the mere 80 kms from Lakeland to Cooktown again took us through a mixture of mountains and grazing lands, with the occasional river crossing to provide certain challenges to the unwary.

And so, on down the last descent onto the flatlands,

and across the Annan River bridge.

The original wooden bridge still lies alongside this new cement edifice. The gates at each end of this old structure are interesting. Despite their solid appearance, and the signs on them which prohibit pedestrian entry to the old bridge, they do not stretch across the entire width of it. Fishermen, both locals and visitors alike, flock to this vantage point over the river. Given that it is also listed in the tourist blurb as a recognized local fishing site, I strongly suspect the prohibition notices are merely designed to protect the local authorities from any liability in the event of a mishap amongst those 'wetting a line'.

The original wooden bridge still lies alongside this new cement edifice. The gates at each end of this old structure are interesting. Despite their solid appearance, and the signs on them which prohibit pedestrian entry to the old bridge, they do not stretch across the entire width of it. Fishermen, both locals and visitors alike, flock to this vantage point over the river. Given that it is also listed in the tourist blurb as a recognized local fishing site, I strongly suspect the prohibition notices are merely designed to protect the local authorities from any liability in the event of a mishap amongst those 'wetting a line'.

This sharp, steep descent to the crossing of the Little Annan River is a case in point,

and the unfenced, rough narrow bridge demanded a speed reduction to 20 kph for safety,

but what a spectacular sight greeted us as we made our crossing. We did note with interest that there are height markers on the bridge which indicate that the water can come over the roadway at up to 2 metres. That would be worth seeing.

and the unfenced, rough narrow bridge demanded a speed reduction to 20 kph for safety,

but what a spectacular sight greeted us as we made our crossing. We did note with interest that there are height markers on the bridge which indicate that the water can come over the roadway at up to 2 metres. That would be worth seeing.

Beyond the Little Annan the Mulligan Highway snakes down past the extraordinary Black Mountain. And it is aptly named...a tumble of large, black rocks piled all the way down the mountainside.

I decided that the sign located at the lookout point described the formation of this geological phenomenon much better that I could.

And so, on down the last descent onto the flatlands,

and across the Annan River bridge.

The original wooden bridge still lies alongside this new cement edifice. The gates at each end of this old structure are interesting. Despite their solid appearance, and the signs on them which prohibit pedestrian entry to the old bridge, they do not stretch across the entire width of it. Fishermen, both locals and visitors alike, flock to this vantage point over the river. Given that it is also listed in the tourist blurb as a recognized local fishing site, I strongly suspect the prohibition notices are merely designed to protect the local authorities from any liability in the event of a mishap amongst those 'wetting a line'.

The original wooden bridge still lies alongside this new cement edifice. The gates at each end of this old structure are interesting. Despite their solid appearance, and the signs on them which prohibit pedestrian entry to the old bridge, they do not stretch across the entire width of it. Fishermen, both locals and visitors alike, flock to this vantage point over the river. Given that it is also listed in the tourist blurb as a recognized local fishing site, I strongly suspect the prohibition notices are merely designed to protect the local authorities from any liability in the event of a mishap amongst those 'wetting a line'.

So here we were at last, almost into Cooktown. The expectation of it all. Would our adventure to the most northerly town on the east coast of Australia fulfil our expectations?

After our first four days here the answer is a resounding 'yes', probably best demonstrated by the fact that we have booked an additional two nights here at the Cooktown Caravan Park, one of four parks in the town.

Ours is located on the final stretch of the Mulligan Highway, approximately one and a half kms from the CBD where sites in a 'rainforest setting' are offered to weary travellers. And we think have the pick of the bunch!

Whilst the front of our patch is somewhat dry and dusty, particularly on the entrance roadway, our rear 'beer garden' is a treat. Good grass, plenty of room for the washing line and shrubs to boot. Compared to many other sites in this park we have oodles of room. Not only that, we are a mere ten metres from the showers and but twenty from the office area, where the regular 1700 hours 'happy hour' is a feature of this park. Blowing dust was an initial problem, but now that all our shade cloth is in place, we are more than set.

We actually chose this park on the basis of the advertised claim that it is completely free of sandflies. In Cooktown, this is something to be cherished. And, to date, not a bite, which, given my extreme reactions to these menaces, is a real bonus.

Whilst there is no doubt that the park could be described as somewhat 'rustic', (complete with feathered residents) and is somewhat lacking in BBQ facilities and the like, our hosts Mary and John Noonan, could not be more accommodating and informative.

Whilst there is no doubt that the park could be described as somewhat 'rustic', (complete with feathered residents) and is somewhat lacking in BBQ facilities and the like, our hosts Mary and John Noonan, could not be more accommodating and informative.

They actually join the happy hour throng each evening and have proven to be a great source of local information (and a bit of gossip). This sort of thing can make all the difference to a stay, if, as it is for us, discovering as much as possible about the town and the local area is important.

As another important bonus, Max just loves the place. His daily skink hunts wear him out in no time at all. However, despite his best efforts, he remains completely inept in the hunting department. As I am sure I have previously mentioned, I am convinced he would starve in the wild.

Of all the things Cooktown may be (including bloody windy), big is not one of them. But it is fascinating and just dripping with history.

As another important bonus, Max just loves the place. His daily skink hunts wear him out in no time at all. However, despite his best efforts, he remains completely inept in the hunting department. As I am sure I have previously mentioned, I am convinced he would starve in the wild.

Of all the things Cooktown may be (including bloody windy), big is not one of them. But it is fascinating and just dripping with history.

This panoramic shot (which I filched from the net....I had no hope of emulating this sweep from Grassy Hill) shows the township nestled alongside the mouth of the Endeavour River below Mount Cook.

Grassy Hill, from which this picture was taken, provides a wonderful vantage point from which to look out over the town and its surrounds. It also provided Captain James Cook a similar view in June 1770, but was then important for a vastly different and far more critical reason.

Grassy Hill, from which this picture was taken, provides a wonderful vantage point from which to look out over the town and its surrounds. It also provided Captain James Cook a similar view in June 1770, but was then important for a vastly different and far more critical reason.

I struggled a bit trying to decide just how I would present our Cooktown adventure. I have settled on doing so on the basis of the four various phases of its discovery and development, which I have realised are quite distinct periods in the history of the town and surrounding areas.

Obviously this begins in June 1770, when Cook struggled into the mouth of the river in his ship HMS Endeavour. As I am sure most Australians would know, Cook's voyage of discovery north along the east coast of Australia almost came to grief when his ship ran aground on a sharp jagged piece of the Great Barrier Reef at a point near Cape Tribulation (which he named accordingly).

His initial attempts to re-float the vessel on the next high tide were unsuccessful. It was then that Cook took the decision to lighten the ship by jettisoning most of the cannon, spoilt stores, ballast and ship's water. This really was life and death stuff. The entire crew were facing a slow and cruel death if Endeavour could not be shaken free of the grip of the coral.

On the next high tide, with the assistance of some clever use of anchors and pulleys, Endeavour was literally yanked off the reef by her crew, but as could be expected, suffered a significant breach of her hull in the process. Despite frantic efforts on the pumps, at which even Cook himself took his turn, the water was gaining constantly. Things were grim until one of the young officers suggested that they 'fother' the ship's hull. A sail, impregnated with a tarred fibre known as oakum, was drawn under the hull and tied in place. With the water pressure pressing the fabric into the breach (which was further plugged by a lump of the coral which was broken off in the timber), this tactic was successful in sealing the hull sufficiently to allow Cook to sail on looking for a suitable spot at which to beach his vessel for repairs.

As we all know, Cooktown now stands on the site he chose. Cook faced a further problem

once he had entered the mouth of the river. To reach the southern bank where he eventually careened the ship, the ship had to again be hauled along on its anchors which were dropped in front of it by longboat.

But finally, here they were, relatively safe, and at a location where, over the next seven weeks, the ship was repaired, water replenished, and the sick in the ship's company were able to rest and recover.

During this time, the botanists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander collected and recorded over 200 new plant species whilst the ship's artist, Sydney Parkinson, was the first European to record the appearance of the local Aboriginals from direct observation.

The relationship between Cook's crew and the locals was apparently cordial. In fact Cook learnt a few words of the local dialect and was the first white man to see a kangaroo which he named 'kangooroo', or 'kanguru', taken from the local name 'gangurru'.

I previously mentioned the significance to Cook of Grassy Hill (seen in the previous picture rising behind Endeavour). He climbed it on several occasions where, from the summit, he was able to make out enough of the reef pattern to plan a route north out of the river mouth to the open sea.

As a compete aside, I had noted in some of Cook's journal entries that he found the climb relatively easy across grassy slopes covered with sandy soil. The entire slope of Grassy Hill is now heavily timbered. I found the answer to this apparent conundrum lies in the fact that in Cook's time the local Aboriginals would fire the hillside to manage the land. This practice ceased with the arrival of white settlers and the woody plants took over.

Cook eventually limped north to Batavia where Endeavour was properly repaired for its onward voyage, and, as we know, he claimed the land he had discovered for England.

In addition to the name of the town, Cook's association with Cooktown is acknowledged with this statue erected in the park on the southern bank of the Endeavour River estuary,

together with this quite majestic monument to be found nearby.

Although others ventured into the area, during the early to mid 1800's, Cooktown's genesis as a township actually lies, not here, but at Palmer River, some 100 kms to the south-west, where (yes you've guessed it) gold was discovered in 1872.

To quote from the tourist booklet, "the establishment of a port for the movement of supplies [became] a priority. The Endeavour River was chosen and the SS Leichhardt landed the government survey team, a part of police, the new Gold Commissioner and 60 miners on its muddy shore on 25 October 1873.

Most of this group set off almost immediately to blaze a road to the goldfield, whilst behind them, on the banks of the Endeavour, the first tents and pre-fabricated buildings began to appear. By February 1874 'Cook's Town' was booming with hundreds of wood and iron buildings on both sides of a two mile length of Charlotte Street. Stores, licensed pubs and banks could be found along with gambling and opium dens in the Chinese quarter of town."

By the end of 1875 there were an estimated 15,000 miners on the Palmer, of which 10,000 were Chinese. A monument to their involvement in the establishment of Cooktown now stands near the wharf area.

During their heyday, between 1873 and 1890 when the gold ran out, the fields of Palmer River and nearby Maytown yielded over 15,500 kgs of this precious metal. It is estimated that the resident population of Cooktown hovered between 3,000 - 4,000 and its port saw so many vessels only Brisbane had more at the time.

And, again typically of the time, the miners and others had a thirst. By 1874, Cooktown boasted 47 pubs and a number of illegal sly grog shops. As the blurb also notes, "with a pub literally on every corner, a large floating population and only shipping as transport out, the town had a very colourful early life".

But of course, notwithstanding the penchant of many to survive on grog alone, a good water supply was critical to the development and maintenance of the town.

One of the great advantages of the area around Cooktown lies in the fact that good drinking water can be found underground, but close to the surface. A large town well was sunk from which water was made available, not only to the town population, but to the many ships which serviced the area, or were in transit up and down the coast. A reticulated water supply has now replaced the main town well, in which a fountain has been erected.

Of the many Chinese who flocked to the area, a number chose to develop market gardens to supply the populace with fresh vegetables and other produce. Interestingly, and in common with many other goldfields, a simmering antagonism existed between the Chinese and the European population who resented their presence. This tension was apparently forgotten on a weekly basis when the market gardeners came to town to offer their wares to the resident matrons. The need for food can always be guaranteed to drive pragmatism!

The Chinese population was so large, that in 1887 an official Chinese Commission (pictured here in Charlotte Street) visited Cooktown for the purpose of ensuring that their living conditions were adequate. What they could have done about it if not satisfied remains a moot point, but in any event the General who led the group was more than happy with what they found. It is recorded that the locals actually formally cheered the Commission who then departed rejoicing. Another international incident avoided!

In the late 1800's the decision was taken to join Cooktown to Laura, a town some 110 kms to the west, by rail. As has been the case elsewhere, by the time the line was commissioned, and an alternative transport route out of Cooktown was developed, the gold ran out and the town fell into decline. The rail link was maintained however until 1961 when it was replaced as an access route by the Peninsular Development Road.

The old Cooktown railway station building now serves as the home of the Cooktown Creative Arts Association.

Mind you, as this photo on the southern approach to the Annan River bridge shows, the Peninsular Development Road was just that!

Another stand-out feature of modern Cooktown which owes its development to the foresight of the town's forebears, is the Botanic Garden. Established in 1878, this extraordinary 'dry tropics' garden houses many of the plants originally collected by Banks and Solander in 1770. The current curator, Sandy Lloyd, has done wonders to also introduce a range of native food plants and develop a wetland area. The orchid house is home to many species, including the 'Cooktown Orchid', the floral emblem of Queensland.

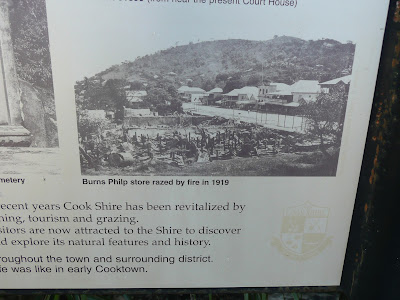

The decline of the town after the gold ran out in the late 1880's was further hastened by the destruction caused by two major fires, one in 1875 and the second in 1919, when great swathes of the main streets buildings were razed (as shown on this main street plaque).

.

Between the fires, further damage was wrought on the town by a major cyclone which hit in 1907. One of the buildings to suffer significantly was the Sovereign Hotel, which lost 50% of its infrastructure. With an admirable stoicism the locals christened it from that point as 'The Half Sovereign'! Its replacement namesake is now the largest building on Charlotte Street.

It has been the venue of a couple of periods of revelry by your correspondent, his goodly spouse and newly acquired park friends where, on one occasion, superior lamb shanks, a surprisingly good red (it should have been for $41 per bottle....this became our allocated once a fortnight splurge) and an excellent local band made for a very jolly evening indeed.

The advent of WW2 saw the evacuation of the civilian population of Cooktown. By 1942 the entire white population had moved south voluntarily. The Aboriginals of the nearby towns of Hope Vale and Bloomfield were less keen to relocate and had to be forcibly removed. Many never returned. Sound familiar? To add insult to injury, the Lutheran missionary at Hope Vale was interned as an alien of concern, being of German descent.

Over 20,000 Australian and US troops were sent to the area where the airfield and a large radar installation on the forward side of Grassy Hill later played a crucial role in the Battle of the Coral Sea.

With the war won, and the troops departed, Cooktown continued to struggle to survive. Another destructive cyclone in 1949 did little to enhance the 'joi de vie' of those remaining.

In the story of what I have chosen to call the 'fourth phase' of the history of Cooktown, we'll have a look at the town as it now is and the industries which have accounted for its economic survival and development. But for now, I am 'blogged out' and you have probably had enough for a whilst as well. More in a day or so.

Over 20,000 Australian and US troops were sent to the area where the airfield and a large radar installation on the forward side of Grassy Hill later played a crucial role in the Battle of the Coral Sea.

With the war won, and the troops departed, Cooktown continued to struggle to survive. Another destructive cyclone in 1949 did little to enhance the 'joi de vie' of those remaining.

In the story of what I have chosen to call the 'fourth phase' of the history of Cooktown, we'll have a look at the town as it now is and the industries which have accounted for its economic survival and development. But for now, I am 'blogged out' and you have probably had enough for a whilst as well. More in a day or so.

No comments:

Post a Comment